Analog

Analog

Analog Days Revisited

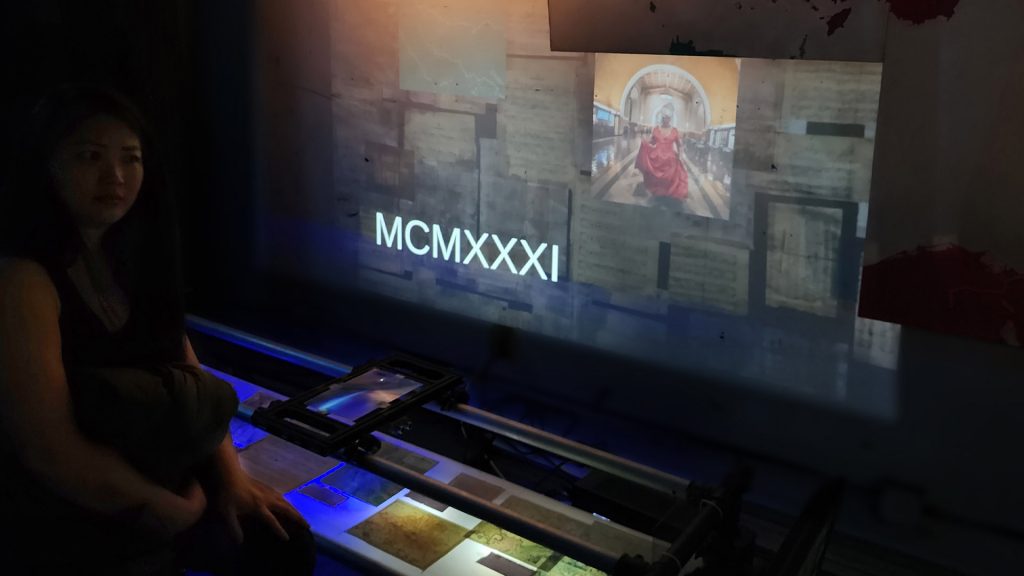

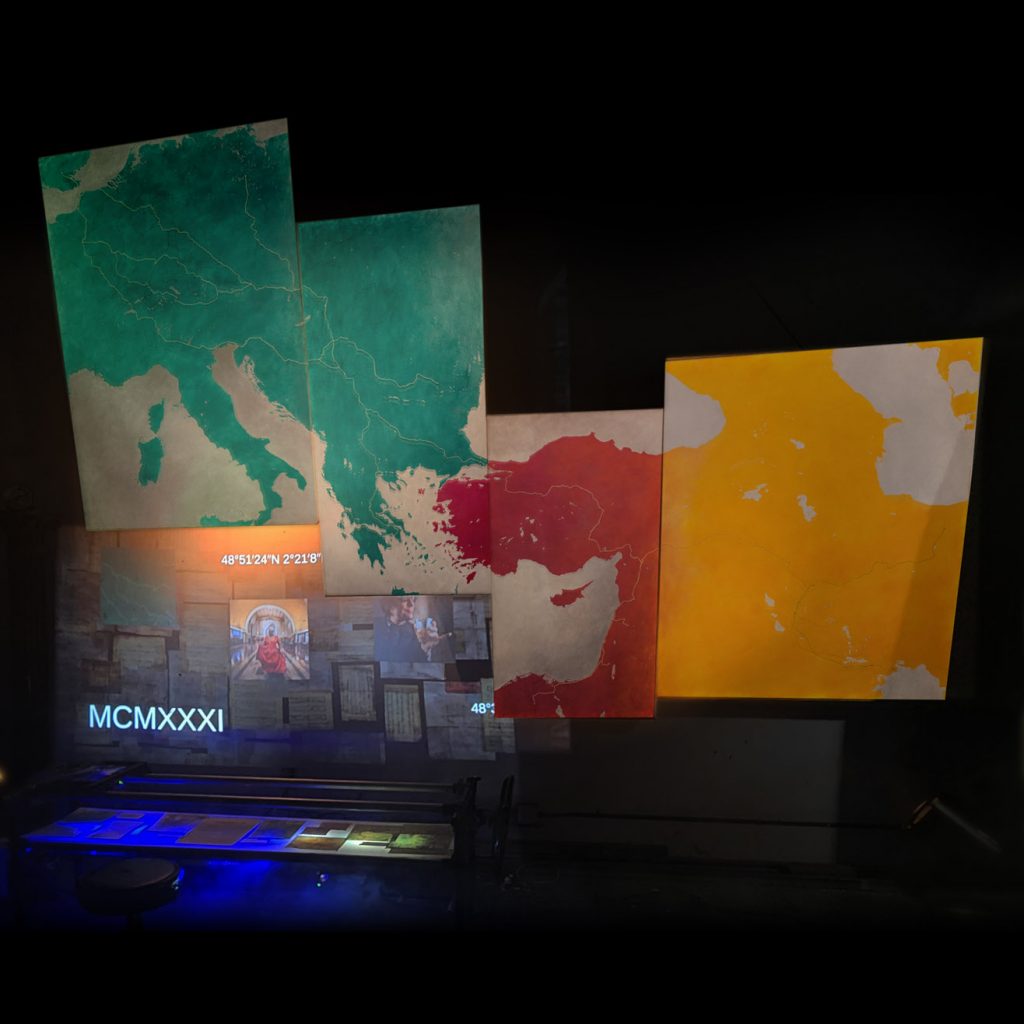

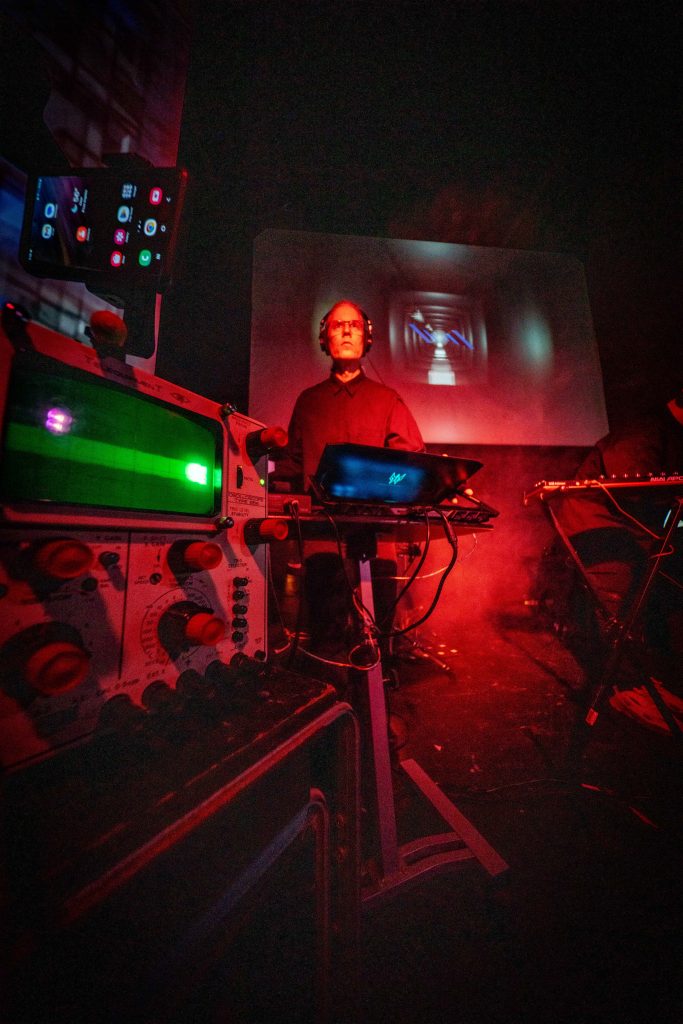

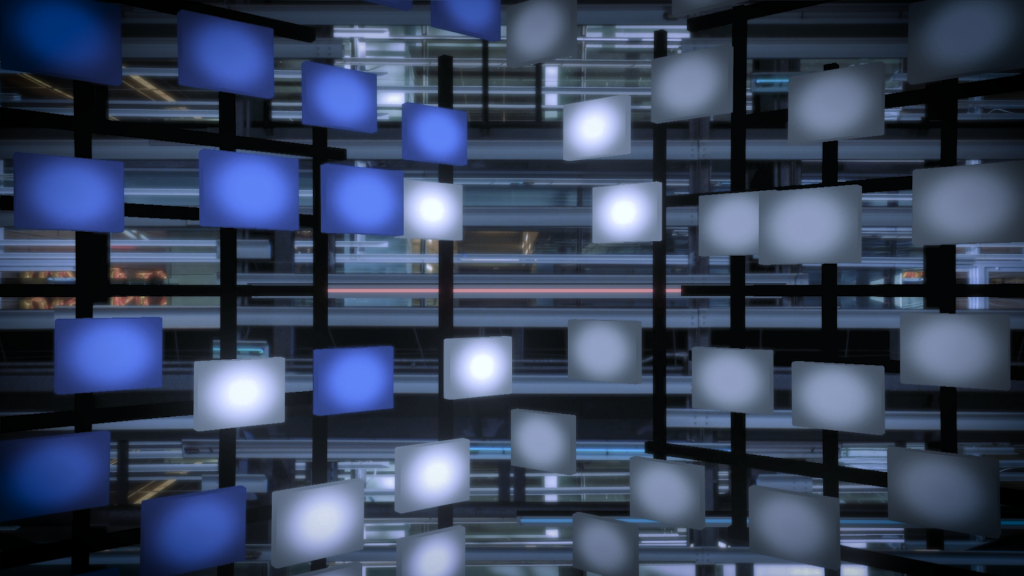

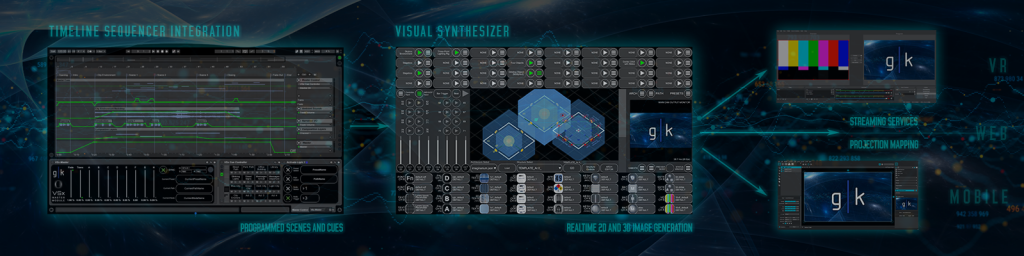

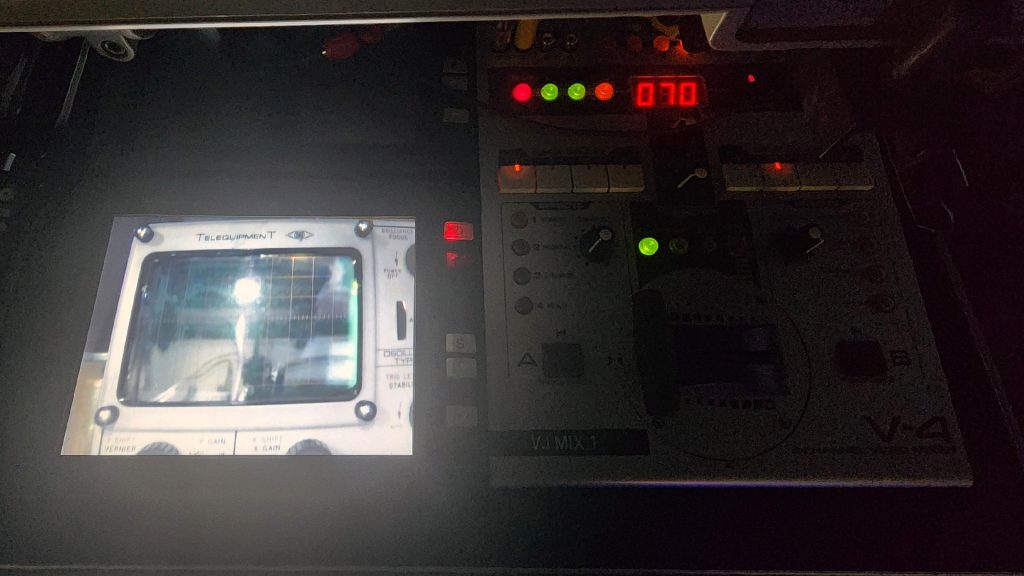

There’s something charismatic and nostalgic about old NTSC video and CRTs. So for the Spring 2024 Brewery Artwalk we decided to relive the old days by firing up some components of the old analog rig (including two Roland V-4s and a vintage Panasonic switcher) and pushing some old-school style media through it.

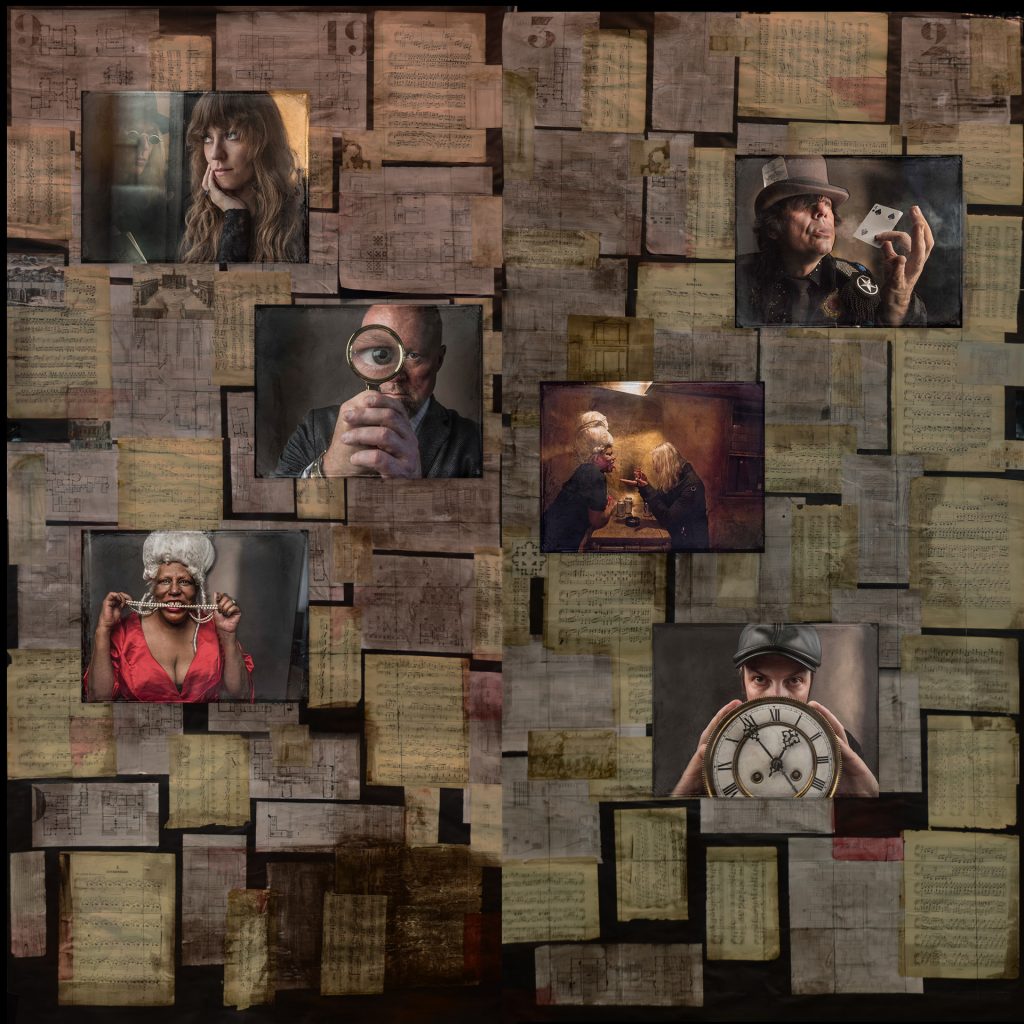

Note the display that is formatted for 1:1 aspect ratio. The square format was (and still is) a favorite way to work.

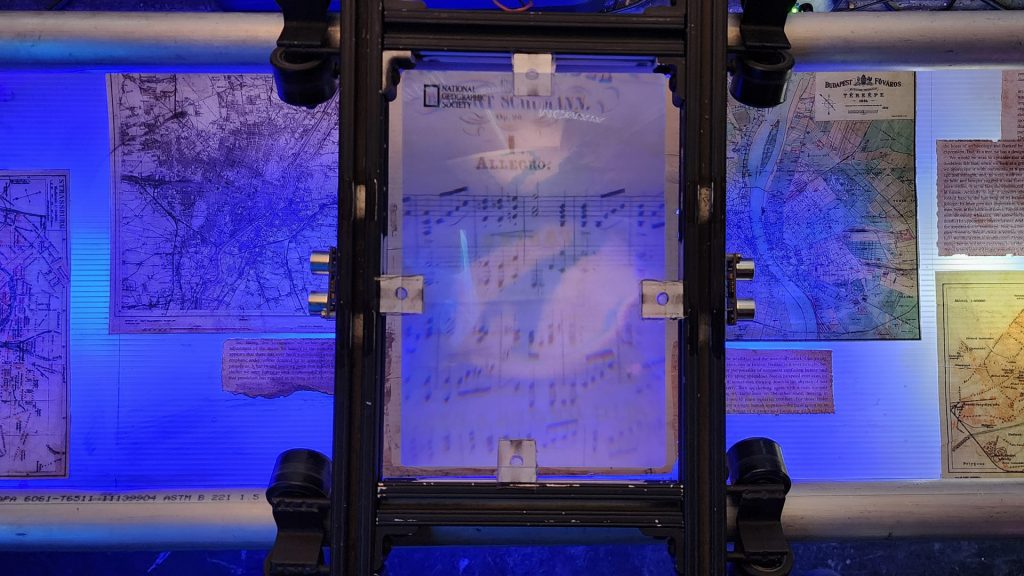

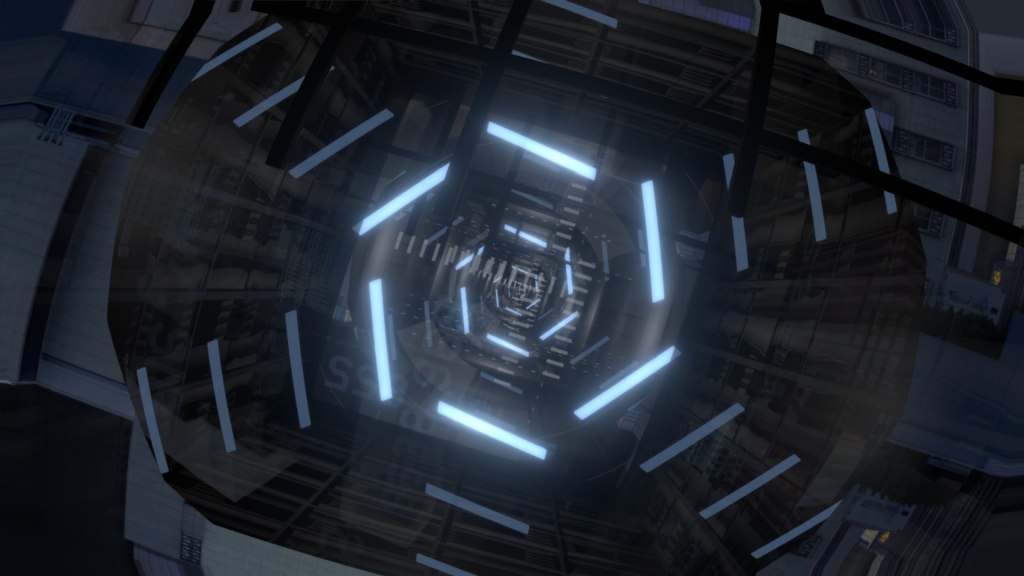

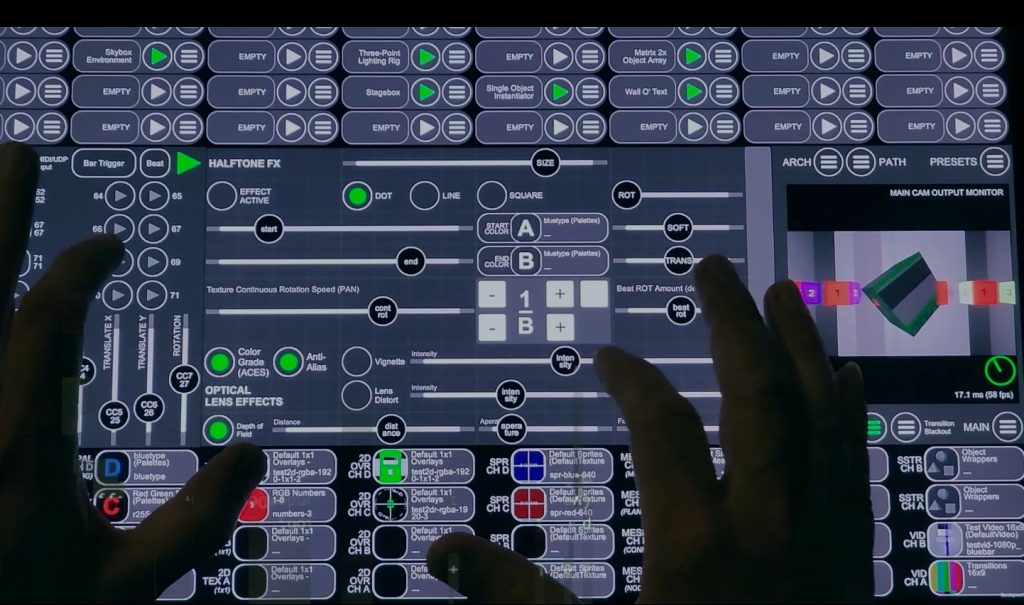

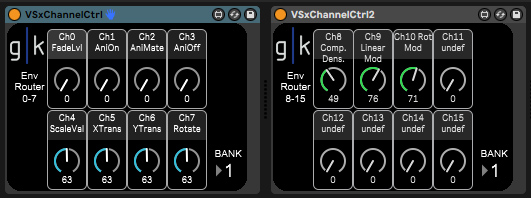

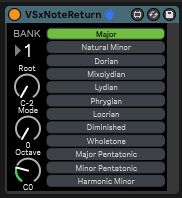

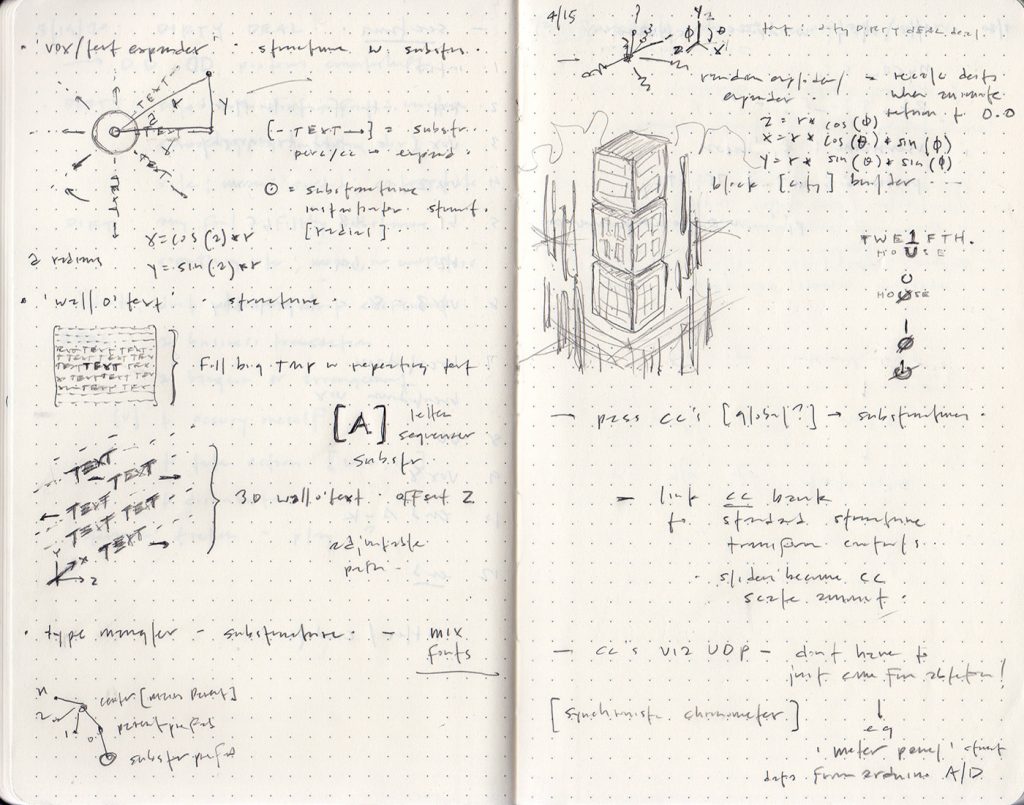

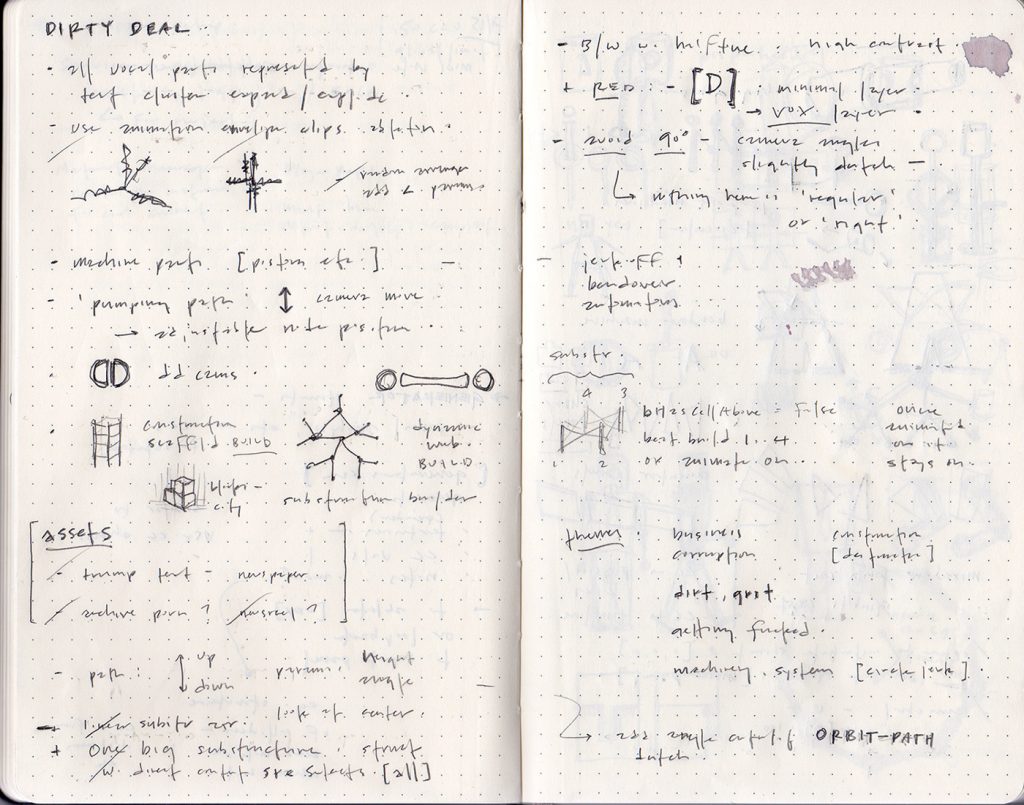

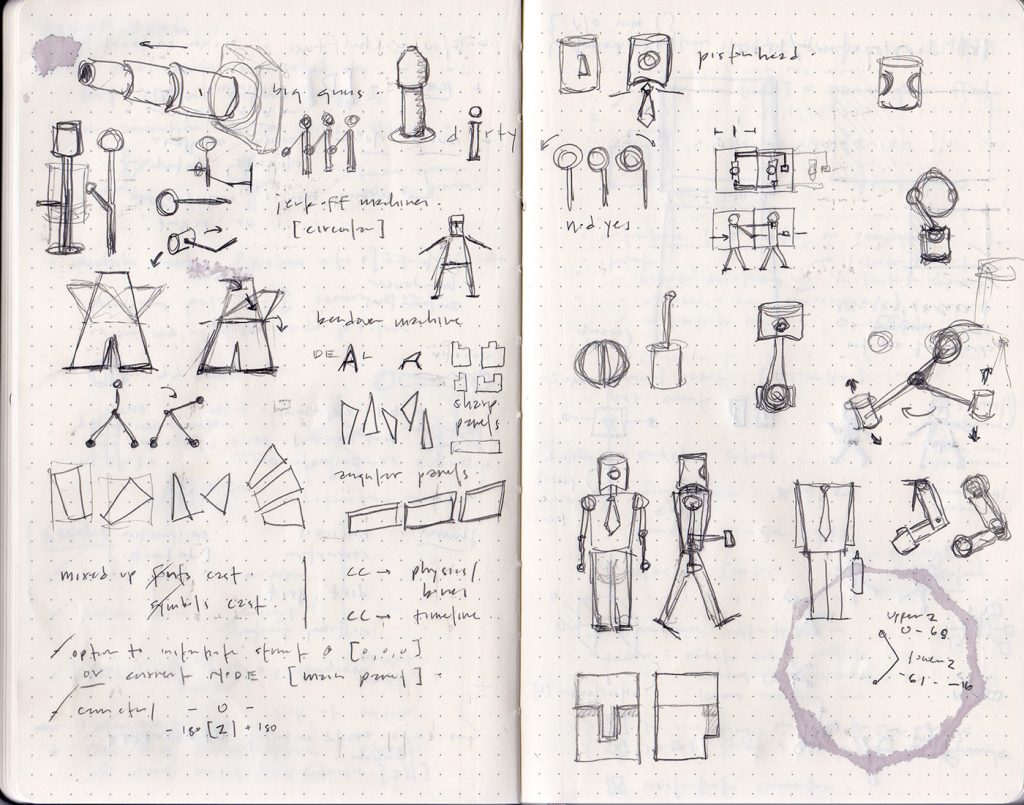

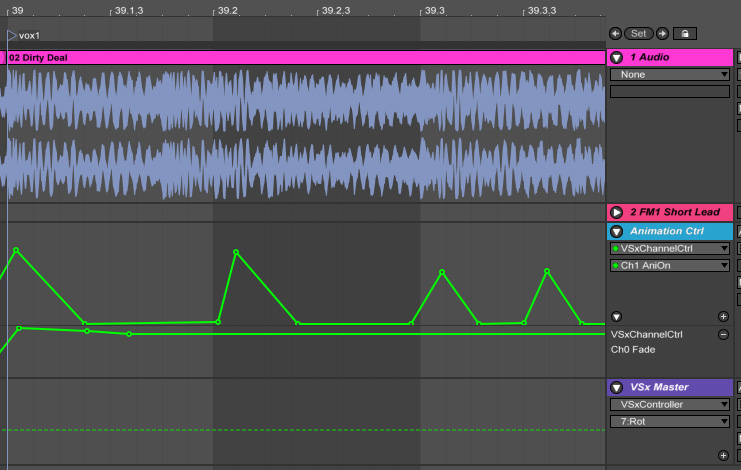

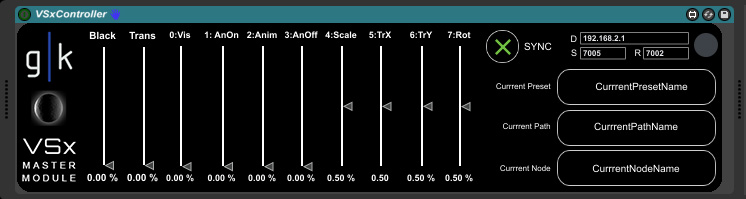

The old analog rig included the early version of the visual synthesizer that eventually evolved into VSx.

Here, updating the rig with the new tool while keeping it nostalgic, a stripped-down version of VSx is running on this modified Atari VCS (a pretty capable graphics machine) — this combo holds some interesting possibilities for exploration in the future!